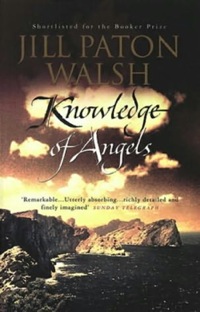

If you’re lucky, you’ll be familiar with Jill Paton Walsh as an excellent children’s author. If you’re unlucky, you might have come across her continuation of Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey novels. You’re much less likely to have run across her original adult novels, despite the fact that they’re all good, and Knowledge of Angels is terrific.

Knowledge of Angels is interstitial and genre-defying. It’s historical fiction, unquestionably. It was published as mainstream (and nominated for a Booker), but it’s also definitely fantasy. It’s not very comfortable in either category. It’s set on “an island somewhat like Mallorca but not Mallorca, at a time somewhat like 1450, but not 1450.”

This would make it Ruritanian, with Grandinsula just an extra island in the Mediterranean, except that onto the shores of Grandinsula is washed up a visitor from another imaginary country, Aclar. Aclar, from what we learn of it, is something like Plato’s Republic and something like the modern world. Palinor is a king of Aclar, an engineer-king, and a convinced atheist. The novel is about what happens to Palinor, and parallel to that runs the story of Amara, a wolf-child rescued on the mountain. This is a beautifully written, passionately concieved story peopled with very real medieval characters, that’s deeply concerned with faith and reason and belief. It’s a philosophical fantasy, and it is in an unusual way a first contact novel.

The book begins by asking us to contemplate an island, and then describes the geography of the island, and then goes on:

At this height your viewpoint is more like an angel than that of any islander. But after all, the position of a reader in a book is very like that occupied by angels in the world, when angels still had any credibility. Yours is, like theirs, a hovering, gravely attentive presence, observing everything, from whom nothing is concealed, for angels are very bright mirrors.

This is the “knowledge of angels,” the complete knowledge a reader of a novel or an angel can have, but which cannot be available to anyone within the limited world of the story. This is a novel that’s aware of the position of the reader, and aware of the world in which the story is being read, as well as the world within the story, which it does not leave again.

Severo leaned eagerly, closely, over the map. He found the Garden of Eden and the Tower of Babel and the burning bush from which God spoke to Moses.; he found Constantinople ,and the lands of the Great Khan, and the Pillars of Hercules, and Ultima Thule. Red letters denoted the Pyramids, the Hangins Gardens of Babylon, the Tomb of Mausolus, the Colossus of Rhodes, the temple of Diana of the Ephesians, the statue of Jupiter at Athens, the lighthouse at Alexandria. Gold letters pointed up the Cave of St John’s revelation at Patmos, the mountain of the Ascension, the Sea of Galilee, St Peters at Rome, St James of Compostela. Porphyry and silver marked the whereabouts of every fragment of the True Cross. An arrow marked the line set out by a lodestone. He could not find Aclar. Neither, when consulted, could the Keeper of Books. They both scanned for some time, reading every word on the surface of the great map, in vain.

At last Severo straightened, and sighed. Then something struck him. “Where is Grandinsula?”

“Not shown, holiness,” the Keeper said.

“Why not?”

“Well, we are a small island and nothing of importance has happened here.”

“Where was this map made, then?”

“Here in this very library, I believe.”

“Ah,” said Severo, baffled. “And when was it made?”

“Long ago, holiness. In a time of wisdom, but before my time.”

Severo is prince and cardinal of Grandinsula, he lives a simple harmonious life within his vows. Beneditx is a famous scholar monk. Josepha is an ugly peasant girl who becomes a novice in a convent. Jaime is a shelpherd. Amara is a wolf girl. Fra Murta is an inquisitor. All of their lives are overturned by the arrival Palinor, even those who never meet him. What Paton Walsh does so well is to create the tapestry of island life as a complete and complex web, with people of all classes, with the technology and material culture, as well as the intellectual and spiritual life, and how that differs for people and classes. Severo asks the shepherds if they’d talked to the wolf girl about God, and they reply that he doesn’t figure much in their daily conversation.

The characters are so well drawn that the story of how the shipwrecked king and the wolf girl become part of the inquiry into God seems as real as bread and olives and sunshine. This is a tragedy, but a tragedy with a great deal of sunshine along the way. If you like the work of James Morrow you will enjoy this. I find it very immersive, but also quite an emotionally trying read—the first time I read it I was astonished by the end.

Spoilers coming up, because I want to talk about the end:

If this is a tragedy, it is Severo’s tragedy as much or more than Palinor’s. Palinor’s faith that God is unknowable is tested to destruction and his own death; Beneditx loses his faith, but it is Severo whose hubris destroys everything. Severo tests God, by way of Amara—if Amara knows God, after having been brought up by wolves, then knowledge of God is innate, and Palinor belongs to the Inquisition. All the characters and their motivations are so well drawn that the tragedy is inevitable, as well as the wider revenge implied by the end, when what Amara sees is the ships of Aclar coming to avenge Palinor—or in a way the modern world coming to sweep away the Age of Faith. While this astonished me, it also felt absolutely right, and I was surprised how strongly I wanted the Aclaridians to finish it—this is an island with a lot of good in it, a lot of kindness and beauty, the light as well as the dark, but no, says my heart, go Aclaridians, wipe it off the map.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.